He still looked the same when he smiled. That much endured.

Dementia stole my uncle’s mind, and ALS weakened his body. If a more unfair circumstance exists in this world, I’m not aware of it. Yet for all that Jim Caple lost in his final years and months, he still perked up when visitors arrived. His wife, Vicki, swears he could sense it. And that smile. The last time I saw him, it stuck on his face, as if it were the only way he knew to signal how happy he was to see me.

It’s what I’m thinking about today, as we mourn the loss of my favorite sports writer.

Maybe he was yours, too.

Jim died Sunday evening, Vicki by his side as he took his final breath, and god damn, I still can’t get my head around it. My uncle was a brilliant writer, imaginative and wickedly funny, an original member of ESPN.com’s irreverent, humor-based Page 2. He was a world traveler, an avid cycler, a voracious reader, a thoughtful gift-giver, an unassuming, empathetic guy who, frankly, should be kicking himself for not coining the phrase, “be curious, not judgmental,” before Ted Lasso ever could.

“He loved everybody,” Vicki said. “He was the most inclusive person I know. He taught me to be more inclusive and not so judging. He never talked smack about anybody, he didn’t feel the need to throw anybody under the bus.”

He was always learning, always wondering, always recommending the book he’d just finished reading. My uncle was a role model in the truest sense — for how he went about his job, yes, but also for how he treated people. He loved my aunt the way every man should love his wife, celebrating her successes and telling the world that she was the best thing that ever happened to him.

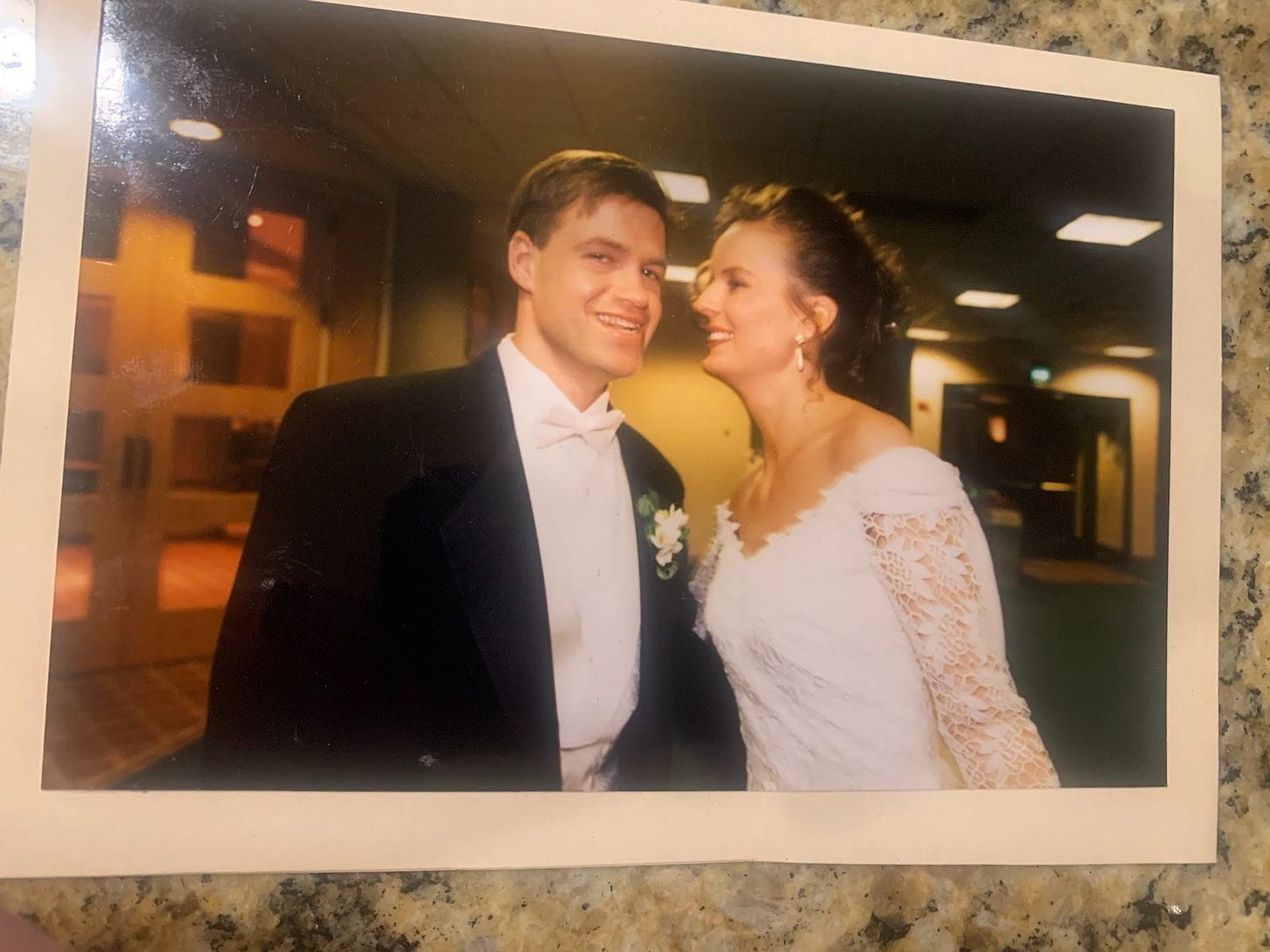

Who knew complaining in the press box could land you a life partner? Early in his career, covering the Minnesota Twins for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, Jim lamented to a colleague that his work schedule made dating impossible.

“I know just the girl for you,” Bob Sansevere replied. He dialed Vicki Schuman and handed the phone to Jim. A month later, they met for the first time at a movie, on a double-date with Bob and his wife.

All these years later, Vicki believes she made a critical error. “I brought my best-looking girlfriend,” she said. “What the hell am I doing?”

“I never even saw her,” Jim would say. “I just saw you.”

You should see the letters he wrote to her from the road. Jim also was a talented artist, and his correspondence often included hand-drawn illustrations of Donald Duck or other creations. Once, on a printout of the poster for Nora Ephron’s “When Harry Met Sally,” Jim photoshopped his head onto Billy Crystal’s character, photoshopped Vicki’s head onto Meg Ryan and taped over the title: “When Jim Met Vicki.”

In a letter dated Valentine’s Day, 1992, above a drawing of Donald Duck dreaming about Daisy, Jim wrote about how he always detested the holiday, “and when I saw folks scurrying around, buying cards and gifts for their loved one, I wanted to pour boiling chocolate over them out of sheer jealousy. But not this year. For this year I am blessed with the most loving, wonderful woman of them all. You. I spend my days counting my blessings.”

They married February 2, 1996, on the coldest day in Minnesota history. A computer programmer at the time for Northwest Airlines, Vicki made Jim’s world bigger. She encouraged him to travel outside the United States, and later joined him on several international work assignments for ESPN — including, of course, the World Wife Carrying Championship in Sonkajarvi, Finland. They shared a love of the Olympics, Jim’s favorite sporting event. Vicki always bought her own ticket, and became Jim’s go-to source for information on scalper pricing and pin trading. Sometimes, she wound up in his columns. Over the years, she received more than one photo credit on ESPN.com.

Christmas was their favorite time of year. Jim gave Vicki a different gift every day from December 1 through Christmas Day, each wrapped in a paper bag with airmail stickers from different European countries. She gave him Easter eggs filled with candy and different figurines. Vicki kept a meticulous December calendar to track their myriad traditions. Every year, they’d pick out their own tree and carry it on their shoulders back home.

They vacationed in Maui each winter, made frequent trips to Europe — Paris, especially, became a favorite — and it was Jim who introduced me to the world of stockpiling airline miles and hotel points, just as Vicki had taught him (“San Diego? Those miles can get you all the way to Australia!”).

Counting the United States, Jim visited 70 countries. Vicki’s at 73. Maybe someday, she’ll make it to Cuba, Denmark, South Africa or Zambia, the only four on Jim’s list that she’s never been to.

Jim covered sports on six continents, though he never did find a way to get to Antarctica. That’s on the short list of things he didn’t do in a career that would have made for a perfect Jim-style memoir. If the whole of Jim’s travels and travails were an iceberg, even this lengthy remembrance addresses only that part sticking out of the water. The guy was everywhere, all the time, like if Forrest Gump were a lot smarter and rode bikes.

Nobody wrote quite like my uncle, who eventually left the Pioneer Press to become a national baseball writer at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. While at the P-I, he became a contributing writer for ESPN.com, and took a full-time job there in 2001, writing for Page 2 along with Bill Simmons, Ralph Wiley, Hunter S. Thompson, David Halberstam and a host of others. Jim’s Off Base column became appointment reading for many baseball fans, complete with his box score line of the week and classic box score trivia.

He was a baseball writer at heart, but also wrote more generally for Page 2, and knew that good sports writing is really just about people, anyway. His role evolved into what I consider the very best job in sports writing history. It tickled Jim that he, of all people, got to do what he did, and he was the first person who articulated to me the concept of Impostor Syndrome, even if he didn’t call it that.

“One of these days,” he would say, “someone is going to knock on my door and tell me, ‘OK, that’s it. We’ve figured you out.’”

He was right, I suppose. He was part of ESPN’s big layoff in 2017. But it was a damn good run.

“Jim was always up for, ‘I’m going to go try this,’” said Kevin Jackson, a founding editor of Page 2. “He would do a few things I’d have to go talk to ESPN’s legal team about. ‘This guy is going to go do this thing for us that is very dangerous. Are you guys OK with that?’”

Who else volunteers for the Tough Guy Competition in the English village of Perton, Staffordshire? Jim did. The resulting story won a Sports Emmy.

Who else drives his car out of the garage across from Safeco Field, pulls onto Interstate 90 and thinks, “what if I just keep driving, all the way to Boston?” Jim thought it often enough that he actually did it, in the summer of 2002, navigating the interstate’s 3,390 miles in 17 days, finding sports to write about at each stop, his dear friend Mark “Scooter” Thomas along for the ride.

While working at The Daily, the University of Washington’s student newspaper, Jim and his buddies adorned one corner of the newsroom with a painting of Fenway Park’s Green Monster. On the final stop of his I-90 tour, he watched a Red Sox game inside the real thing.

In March 2005, he toured the campuses of schools participating in the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, soliciting invitations on Page 2 and then staying in dorms and apartments and fraternities and even a sorority. One of the frat houses at Illinois convinced him to wear a Tigger costume to a local bar. There are pictures.

Sit down for an interview with Olympic figure-skater Johnny Weir? Well, sure. But why not do it while getting a mani-pedi at a 5th Avenue spa in New York City?

Lampoon the ubiquitous vuvuzela sounds during the 2010 World Cup? Of course — by attempting, unsuccessfully, to sneak one of the instruments into the MLB All-Star game.

Feature the gluten-free diet of tennis star Novak Djokovic, one of Jim’s favorite athletes? Certainly, but Jim did it by taking on the diet himself, concluding after three weeks: “Meals weren't as filling, so I often remained hungry, but that wasn't bad. Like Tour de France cyclists who embrace the pain of riding 100-plus miles per day for three weeks, you need to embrace hunger.”

He caught a knuckleball from a Cy Young Award winner and batted (but did not hit) against a former first-rounder. He walked the length of an Olympic marathon course. He rode his bike through Seattle with disgraced Tour de France champion Floyd Landis. He watched a Super Bowl in Amish country, covered a Pillsbury Bake-Off, and wrote about horse racing in Dubai. Once, he pedaled to Safeco Field to catch the end of a perfect game and conducted interviews in his cycling outfit. His old college pal, Rod Mar, photographed him nearly nude for a participatory story in espnW’s “The Body” issue. He wrote one book about how much he hated the Yankees, and another about a fictional WWII navigator, based loosely on my grandfather’s experiences.

“Wherever the conventional wisdom was headed,” former ESPN.com colleague and friend Jerry Crasnick wrote, “his mind inevitably wandered in a different direction.”

Jim always asked the important questions. Like when Mariners third baseman Adrian Beltre went on the disabled list with a contused testicle, and Jim pondered in maybe my favorite story of his: if we know getting hit in the nuts is so painful, why do we find it so funny?

“Whenever there was a unique angle,” said Scott Miller, a longtime baseball writer and one of Jim’s closest friends, “we’d always just look at each other and say, ‘that’s one for Jim.’”

Perhaps Jim’s favorite story: a trip to Russia to chronicle the experience of Sue Bird and Diana Taurasi playing pro basketball there. It’s one of a handful of memories that slipped past his illness, and a frequent topic of conversation in his final months.

The dementia diagnosis — primary progressive aphasia, a form of frontotemporal dementia — came in April 2021. He’d lost his sense of direction, no longer able to navigate on trips overseas. In social settings, Vicki was talking more, Jim talking less. It’s always little things at first.

We were crushed. Jim’s mom, my grandmother, had spent her final years afflicted by Alzheimer’s. My dad and his siblings, Jim included, knew what it meant to grieve the living, to watch this person you love slowly become somebody else. It was unthinkable — still is, really — that their little brother would suffer similarly.

As if that wasn’t cruel enough, Jim also developed physical symptoms consistent with ALS. Vicki noticed him growing weaker. He’d stopped riding his bike. Stairs were becoming difficult. At night, when he would hold her, she could feel his fingers twitching. Doctors first expressed concern in July 2021, but Jim wasn’t formally diagnosed until March of this year.

He was inducted into R.A. Long High School’s Hall of Fame later that week. My dad gave a speech on his behalf, recounting the times Jim wrote about his alma mater for Page 2, bringing little old Longview into the national spotlight.

Writing about the proximity of R.A. Long and rival Mark Morris — their head basketball coaches lived on the same street — Jim mused: “Sure, the Yankees and Red Sox have a famously bitter rivalry. But at least Joe Torre doesn't have to drive by Terry Francona's house every night.”

Jim liked to quote Earl Warren, the former Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, who preferred to read a newspaper’s sports section first. “The sports page records people’s accomplishments,” he said. “The front page has nothing but man’s failures.”

My uncle loved to mock and satirize, yes, but he also gravitated toward triumph and joy, marveling at athletes who overcame seemingly impossible odds to reach the pinnacle of their sport — like the great boxer Esther Phiri, whom Jim profiled on a trip to Zambia.

He would marvel, too, at Vicki. We all have.

For a time, she described a perpetual grief cycle — anger, acceptance, crying, an endless loop of sorrow and frustration, all while providing an increasingly demanding measure of care for the person to whom she’d devoted her life. Those feelings never subside, not completely. But my aunt says she found grace in appreciating what time she did have left with her favorite person, and in the joyful memories they still could create.

She learned to “find the helpers,” advice straight from Mr. Rogers, and Vicki knows she is lucky that way. She could afford to pay a caretaker who spent three days each week with Jim — a beautiful soul named Antony, a man to whom our family cannot overstate our gratitude — watching the same shows, listening to the same music, allowing Vicki time to see a movie or run to the store or simply park her car somewhere and sleep. Friends and neighbors and longtime colleagues spent the last several months stopping by Jim and Vicki’s home in Newcastle, Wash., delivering meals and cards and gifts.

She learned to cut his hair. She helped him get dressed. She pureed his foods, she thickened his tea, she danced and sang and talked about his favorite athletes (Sue Bird! Willie Mays!) and actors (Judy Garland!) and friends (Jayson Stark!). She smiled and deflected when the dementia manifested as irritation, and sure enough, Jim smiled, too. She calmed him when he struggled to swallow and didn’t know why. She was there for him, always, her devotion a gift not only to Jim, but to all of us who loved him.

Last Christmas, my mom asked Vicki how she was holding up.

“I can still touch him,” she replied.

Seattle hosted the MLB All-Star Game this year. It brought to town Jerry Crasnick, Jayson Stark and his wife, Lisa, friendships forged through Jim’s time at ESPN, and Jim and Vicki’s friend Mary was visiting from Minnesota. It was a lovely day, sunny but not too warm, and we spent it drinking beer and wine and whiskey on their back deck, Jayson and Jerry swapping stories about their buddy. Vicki had taught Jim to sing “Jayson Stark!” to the tune of “Baby Shark,” and, to Jayson’s delight, we all joined in.

“You could find Jim working on his favorite stories at any hour, day or night, mostly night,” Jayson wrote to me on Monday. “But he always had time for his friends — especially his fellow sportswriters — because he had an ever-present smile, a great heart and a love for the unique camaraderie of our business.”

Jim was past the point of being able to follow conversation, but he couldn’t stop smiling. He knew these were his friends. That’s all he needed.

We all spent some time looking over the keepsakes and memorabilia in Jim’s home office — my favorite room in his house, and only partially because it includes an autographed copy of Jim Bouton’s “Ball Four,” with Jim quoted on the cover flap — and posed for a few photos before company departed. They hugged goodbye the way a person does when they’re seeing a friend for the last time. It was an honor to witness, and I’ll never forget it.

My uncle influenced me in too many ways to count, in ways I probably don’t even realize, from the time I was young until the day he died, and, surely, beyond. Whatever I might be as a writer or journalist is because of the example he set and the wisdom he so eagerly dispensed. More than anything, he made it all seem so attainable, that if one kid from Longview could attend the University of Washington and write for The Daily and make it in this profession, why couldn’t I? Jim spoke about my own career ambitions as a “when,” not an “if.” At the release party for his first book, “The Devil Wears Pinstripes,” he signed my copy and wrote that I had until age 25 to write my own. Didn’t quite make deadline on that one.

Jim covered the Twins when I was a kid, and I thought his job sounded like just about the coolest damn thing in the world. When I was 16, he invited me to shadow him at a Mariners game, from the press box to the clubhouse. Let me tell you: there are few things that could have impressed 16-year-old me more than seeing Dave Freaking Niehaus greet my uncle like they were old pals.

There was no ego, no gatekeeping. Those old writers who joke that the best advice for aspiring journalists is “don’t do it” — Jim would never. He was thrilled that I admired him, and was never too busy to read whatever dogshit story I’d sent him to look over, never failing to offer encouragement in return. Before he filed a big story, Jim might email me two different versions of the lede, asking which I liked better. He was a night owl, and we’d sometimes exchange messages until 2 a.m., discussing the craft or simply exchanging jokes.

I got to see him work up close in the summer of 2009, when I covered the Mariners as an intern for MLB.com. The job didn’t pay that year, so Jim and Vicki invited me to stay at their house, rent free. I declined at first, not wanting to impose. Jim called me the next day. “I insist,” he said.

The next three months were like a coming-of-age movie with no conflict. I drove my uncle’s car to and from the ballpark, and would deconstruct the day’s happenings when I arrived home, usually after midnight, Jim still typing away in his office. He’d make three different phone calls for three different stories one day, and catch a flight to St. Louis or Los Angeles or New York the next. Jim and Vicki included me in their social life, too, inviting me along to outdoor movies or to meet friends at a bar somewhere in Seattle. They were always on the go, always having fun, always in search of the next adventure.

Late in my internship, Jim asked if I wanted to get lunch before a Mariners game. After we sat down, he said: “Hey, I just wanted to tell you what a great job you’re doing. Just keep showing up.”

A few years later, when I worked at The (Tacoma) News Tribune, I’d cover the occasional Mariners game so Bob Dutton, the beat writer, could take a day off. Sometimes, Jim would show up at the park, too, to interview a player or manager or simply work in the press box, just because he liked being at the game.

We’d chat in the clubhouse and eat lunch together. Then I would go write, and he would go write, and it occurred to me only recently that these were some of my favorite days, my uncle and I showing up to the same place to do the same job, like it was the most normal thing in the world.

A few years ago, Jim did some freelancing for The Athletic, overlapping with my time there. I took a screen-shot of the Seattle site’s home page one day. Our bylines were right next to each other.

Jim revered his parents, Verle and Jeannette, delivering the eulogy at each of their funerals. He nurtured close relationships with his siblings: my aunt Margaret, his oldest sister, who often looked after him when he was a small child; his sister Kathy, a librarian and children’s author whom he often visited in the Boston area; and my dad, John. Jim enjoyed that Vicki’s parents, George and Rosalie, had the same names as his own grandparents, George and Rosy. My uncle will be missed, too, by Vicki’s three siblings, Cindy, Greg and Brad, and her nieces Kayla and Katie and nephew Ryan. Jim at least got to spend some time with Kayla’s young son, Cal, and Katie’s young daughter, Antonia. And my uncle loved discussing books and movies with my older sister, Molly, who holds a Master’s in library science and currently works for Flexjet in Cleveland.

My dad and his brother bonded over their love of baseball, once playing together at the Field of Dreams in Dyersville, Iowa. For some reason, they trekked to South Bend together for Washington’s football game at Notre Dame in 2004.

My dad and I made the trip to Cooperstown for Ken Griffey Jr.’s induction in 2016. We planned to sit on lawn chairs in the free section, but as we walked to the ceremony, my phone rang.

It was Jim. He had three tickets in the reserved seating area, not all that far from the stage.

Turns out he knew the mayor.

I saw my uncle last Monday, six days before he died. I knew it would be the last time. He still could walk, though not very far. Breathing and eating had become difficult. The hospice nurse told Vicki that he might leave us any day.

Jim sat at his desk, watching YouTube videos of artists he’d never heard of, the kind of music — country, in fact — he never would have listened to. So I put on one of his favorites, Elton John’s “Rocket Man,” and sat with him as he sang along, at least some of the lyrics still committed to memory.

When he still could operate his phone, Jim liked to show visitors — “if he really loves you,” Vicki said — a video of Sir Elton performing the song at the Tacoma Dome last October. Vicki remembers one afternoon when Jim searched frantically for the video, intent on playing it for an old friend. He found it and began singing at full throat, crying.

I miss the earth so much, I miss my wife

It's lonely out in space

On such a timeless flight

For as long as I live, I’ll think of my uncle when I hear that song. I’ll follow Vicki’s lead, too, and focus more on the joy he brought us, rather than the things that will never be. He didn’t get to know my daughter, but he had a blast at my wedding. He’d have loved every single thing about On Montlake, but he at least got to see me make my way in this profession he so cherished. He never got to write his life story. That’s hard for me to swallow. But he touched so many lives and inspired so many careers — a basketball writer in Los Angeles, a magazine editor in Seattle, a reporter in Las Vegas — that we’ll be telling Jim Caple stories until it’s time to join him in whatever blessed place he is now.

Jim had stopped going outside, even to check the mail or grab the newspaper, but he surprised Vicki as I left last week. She helped him to his feet, and my uncle followed me to the door and out of it, down their front steps and onto the driveway.

He wanted to watch me go.

I rolled down my window and waved until I couldn’t see him anymore.

Vicki told me that no remembrance of Jim would be truly complete without a top-10 list, and so here you have it: the 10 best pieces of advice my uncle gave me.

10. The ultimate icebreaker: ask a ballplayer about his first glove. It’s disarming, and they almost always remember. Jim, of course, made a column out of it.

9. If you’re going to criticize someone in print, show your face the next chance you get. An unwritten journalism rule as old as time, but one that I first heard from my uncle.

8. Marry a girl from Minnesota. I didn’t do this, but that doesn’t make it any less valuable.

7. Student newspaper experience is more important than any journalism class. No offense to my instructors, but man, was this true. Jim loved returning to campus and visiting The Daily’s newsroom. A friend told me Monday that hearing him speak helped shape his own career.

6. Don’t buy the overpriced beer, wine or champagne from the vendors outside the Eiffel Tower. This was honeymoon advice, and it served my wife and I well.

5. Write game stories as if you’re writing a letter to your dad. What would you tell him first? What would he want to know?

4. Injuries are always worse than what the coach/manager lets on. True when Jim was covering baseball, and even more so today.

3. Drink diet soda to kill your taste buds and save calories. I tried this for a time, but it didn’t stick. Fortunately, I don’t drink much soda anymore, anyway.

2. You might not always ask the best question, but you can always be the best listener. I was in college, and he shared this during a talk in The Daily’s newsroom. Jim believed any story could be made better by simply listening to what the other person was saying. Vicki loved this about him, too.

1. Marriott. Always Marriott. Duh.

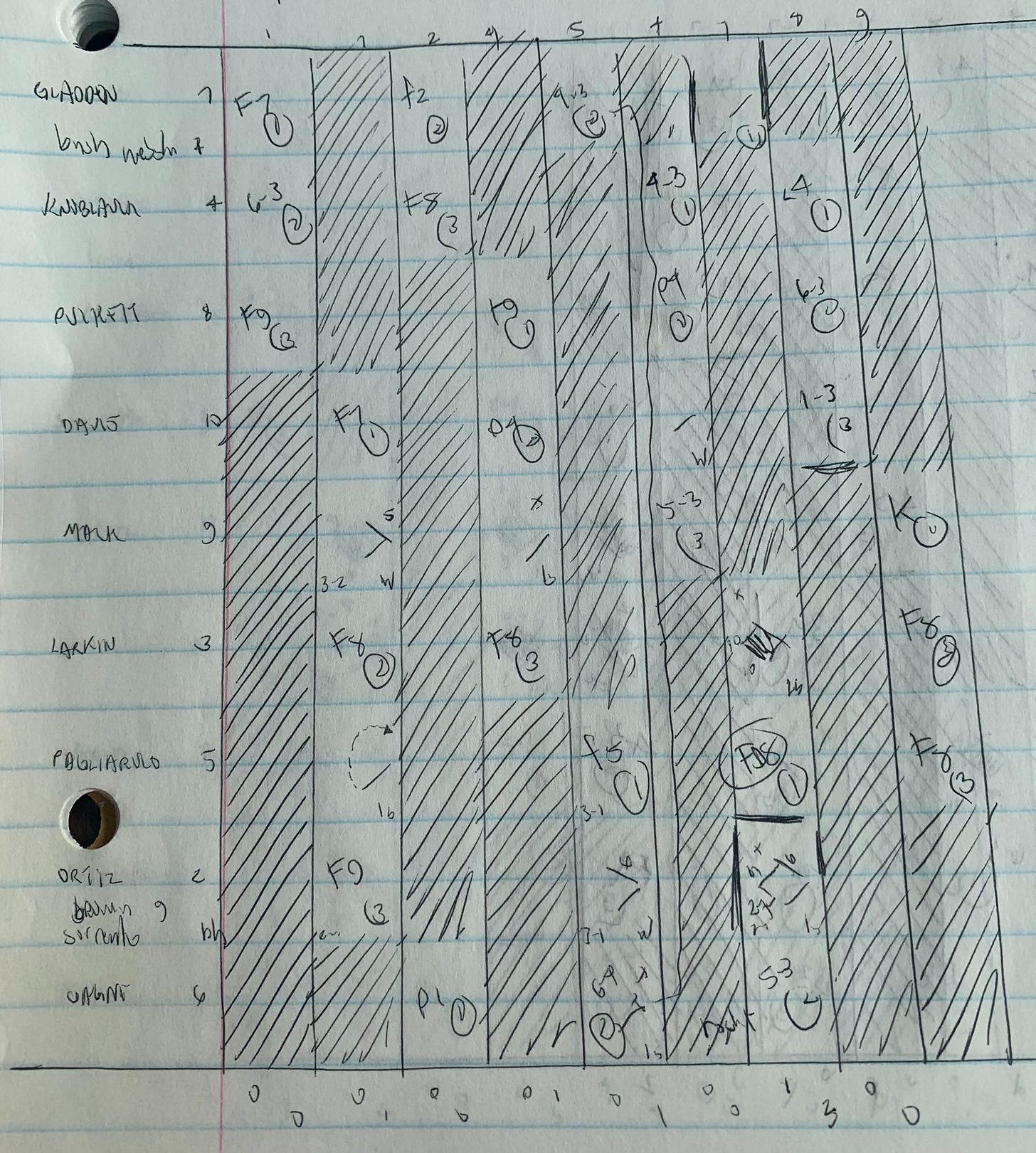

CLASSIC BOX SCORE

Jim loved to dig up old box scores and pose them as trivia, asking readers to identify the historical significance. In honor of his old columns, here is a box score from one of Jim’s very own notebooks. The date: Sept. 29, 1991. Scroll past the photo for the answer.

There are only so many possibilities here. Kirby Puckett and Chuck Knoblauch give away that this was a Minnesota Twins game. You know Jim covered the Twins, and you might know the Twins won the World Series in 1991, which means a late-September game of significance probably had playoff implications.

Indeed, this was the day Minnesota clinched the American League West championship, though they lost the game, 2-1, to the Toronto Blue Jays. A loss by the White Sox that day wrapped up the division for the Twins, who eventually defeated the Atlanta Braves in seven games to win the World Series. Jack Morris pitched a 10-inning shutout in Game 7. That team — and that season — left an indelible mark on Jim’s career. He later stumped for Morris to be inducted into the Hall of Fame (he eventually was, via the Modern Era committee). I know Jim voted for him.

LIES, DAMN LIES AND STATISTICS: Jim covered 12 Olympics and 20 World Series, only one of which was interrupted by an earthquake.

FROM LEFT FIELD: Some folks might know that I tried (and failed) to hit against legendary UW softball pitcher Danielle Lawrie. What you might not know is that earlier the same day, Jim had an extended opportunity, flailing at pitch after pitch after pitch, managing contact just once, a weak groundball to second base. Lawrie wasn’t all that impressed by Jim’s intramural championship, either.

INFIELD CHATTER: “Good news: there’s another game tomorrow.” — Jim, to me, in the Safeco Field parking garage, after I complained about how much I hated the story I had written that night. That was the beauty of baseball writing, Jim said: good or bad, you get to go out and do it again the next day.

— Christian Caple, On Montlake

An extraordinarily moving tribute to your uncle, Christian. You honor his legacy well. May he rest in peace.

He was my favorite sportswriter for years. Page 2 on ESPN.com might have been the very peak of internet sports journalism. I discovered it through Jim.

Frequently I'd write to my brother and father about "that new Caple piece." I still do that now regarding your pieces. In fact, I probably will about this one right here.

You do your uncle great honor by taking up the mantle. It delights me (and I hope it honors you) to be sharing "that new Caple piece" 25 years later.

Impossible to consider Pacific Northwest sports journalism without the Caple name. Thank you.